From the ashes of financial collapse, the K-W Symphony rises

Two years after a devastating financial crisis, the K-W Symphony has been reborn and returns to its performing home, Centre In The Square, for an emotional concert, Luisa D’Amato writes.

By Luisa D’Amato, Reporter

Luisa D’Amato is a Waterloo Region Record reporter and columnist. She writes on issues affecting day to day life in the area. She can be reached at ldamato@therecord.com.

The Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony has found its way home.

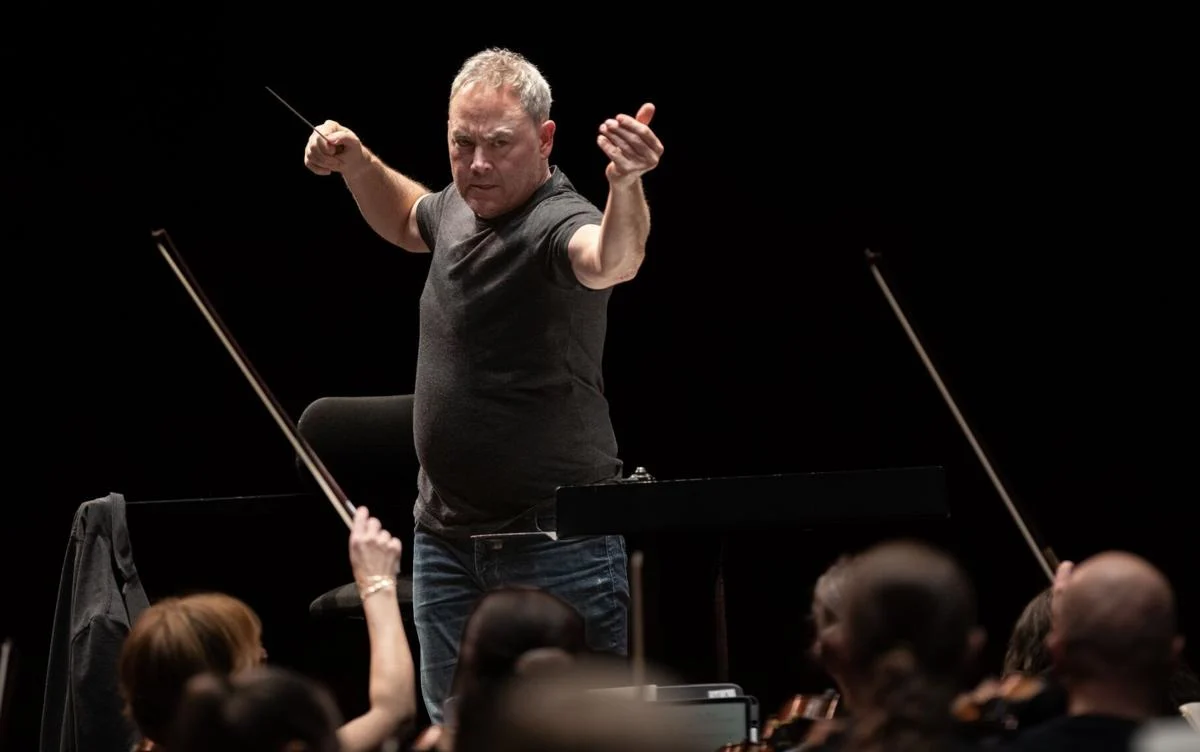

Two years after a devastating financial crisis, the organization has rebuilt and will give a historic performance Thursday at Centre In The Square of Mahler’s Second Symphony, known as the “Resurrection.”

Resurrection, indeed.

The Kitchener concert hall is a beautiful acoustic space, considered one of the finest in North America. The sound is warm and clear, and even the slightest vibration of a harp string carries to the back row.

This is the symphony’s performing home, originally built for that purpose with support from the region’s generous music loving community.

The hall opened in 1980 with a performance of this same monumental “Resurrection” symphony.

The orchestra was the hall’s major tenant until the sudden layoffs of musicians and staff in September 2023, followed by the shocking announcement that the organization was filing for bankruptcy.

There has been anguish, soul searching and hard work over the past two years as the orchestra sought a sustainable future under new management.

This concert, in this hall, marks its rebirth. “It is quite emotional being back in Centre In The Square now, after all we have been through,” said bass player Ian Whitman after the first rehearsal on Tuesday.

Whitman and his wife, violinist Allene Chomyn, lost their jobs when the symphony collapsed in 2023. They and fifty others were informed just days before the new season was set to begin.

The announcement came without warning. There was no chance to negotiate solutions such as a temporary pay cut.

Some musicians were forced to leave the region and find work elsewhere. Many, like Whitman and Chomyn, pieced together income by teaching and freelancing, commuting across southern Ontario to perform. Whitman called it the “401 Philharmonic.”

Musicians also organized community concerts and raised 495,000 dollars through GoFundMe to support performance costs, emergency needs and legal guidance.

The grim numbers emerged slowly. The symphony had been running large deficits even before the pandemic. In 2018 to 2019, the deficit was 730,000 dollars.

When concerts shut down in March 2020, finances briefly improved thanks to government support.

By July 2022, the deficit had been reduced to 200,000 dollars.

In person concerts returned in 2022, but audiences did not. Many were still hesitant to gather in public spaces.

Season subscription sales fell from 8,000 in 2019 to 2,000 in 2023. The symphony hoped for emergency federal funding and renewed support from major donors, but neither materialized.

By late summer 2023, the accumulated deficit had climbed above one million dollars, creating potential personal liability for the board of directors. They closed the organization and all resigned except board chair Rachel Smith-Spencer, who stayed to guide next steps.

Documents later showed the symphony owed 916,183 dollars and had assets valued at 273,620 dollars consisting of the music library, some large percussion instruments and office equipment.

Creditors included ticket and subscription holders owed 706,987 dollars, and forty six families with youth orchestra memberships owed 27,889 dollars.

Some musicians believed bankruptcy could still be avoided. That would allow the symphony to keep its name, charitable status and track record with granting agencies.

Musician Kathy Robertson approached arts supporter Bill Poole, known for leadership roles at the Centre for Cultural Management at the University of Waterloo and the Canadian Clay and Glass Gallery. He would later become chair of the new board.

“If ever I am thanked for saving the symphony, I say it is the musicians who saved the symphony because they refused to let it go,” Poole said.

A new board was elected by ninety three members in June 2024. It held a creditors’ meeting proposing zero cents on the dollar. Creditors accepted.

Meanwhile, the K-W Symphony Foundation, which had continued to operate independently, paid the organization’s only secured creditor, RBC Bank, which was owed 75,000 dollars.

The bankruptcy was officially annulled in October 2024. With a skeleton staff, the new board began reconnecting with donors and granting agencies.

Poole said they received support from the cities of Kitchener and Waterloo and the Region of Waterloo. The Canada Council for the Arts had even held funds for the organization in anticipation of its return. The Ontario Arts Council did not provide funding, which Poole described as a huge disappointment.

Some major donors have returned, although the symphony struggled to retrieve its donor database and could not contact several previous supporters. The organization aims to raise 480,000 dollars by next July and has already secured 250,000 dollars.

“Rebuilding trust was a huge piece of it,” Poole said. “We had to convince people that we are committed to operating in a really responsible way. There has been a lot of wait and see, and I completely understand that. This is a very challenging road.”

The new business model reflects a sharp focus on sustainability. The operating budget is just over one million dollars, about twenty percent of the previous size. All fifty two musicians are now freelancers rather than employees. There are six staff members, and only executive director Jason Doell works full time.

Concert venues have also changed. Centre In The Square is expensive and difficult to fill. There will be only three performances there this season, with most concerts taking place in smaller venues like churches. In 2022 to 2023, the symphony performed forty times in the main hall.

Whitman now works part time as the orchestra’s learning and community engagement coordinator. He is arranging performances in accessible community settings including schools, retirement homes, libraries, local restaurants and possibly Pride festivals and the Christkindl Market.

“We are ready to be of service to the community,” he said. “Things look incredibly hopeful.”

Mahler’s Second Symphony requires a massive ensemble of ninety musicians and a large choir. It is extremely costly to present, but this performance is supported by a major donation from philanthropist George Lange, described as a “Mahler nut.”

(Full disclosure: the choir performing in this concert is the Grand Philharmonic Choir, of which I am the executive director and also a singer.)

At rehearsals this week, you could feel history correcting itself as the sound filled the hall once again.

Mahler’s symphony is a magnificent work that saves its most powerful moment for the end. The choir begins almost imperceptibly, like a breath of wind, rising to a triumphant climax.

“Aufersteh’n, ja aufersteh’n wirst du, Mein Herz, in einem Nu.”

It means: Rise again, yes, you shall rise again. My heart, in the twinkling of an eye.

And so they did.